Robot dynamics (three different ones)

As a roboticist, understanding robot dynamics is essential for designing fast, agile trajectories and controlling potentially unstable, complex robots. In this post, we will explore three types of robot dynamics at a high level and demonstrate how to compute them using the Pinocchio library, which is an efficient implementation of rigid robot dynamics algorithms.

Inverse dynamics

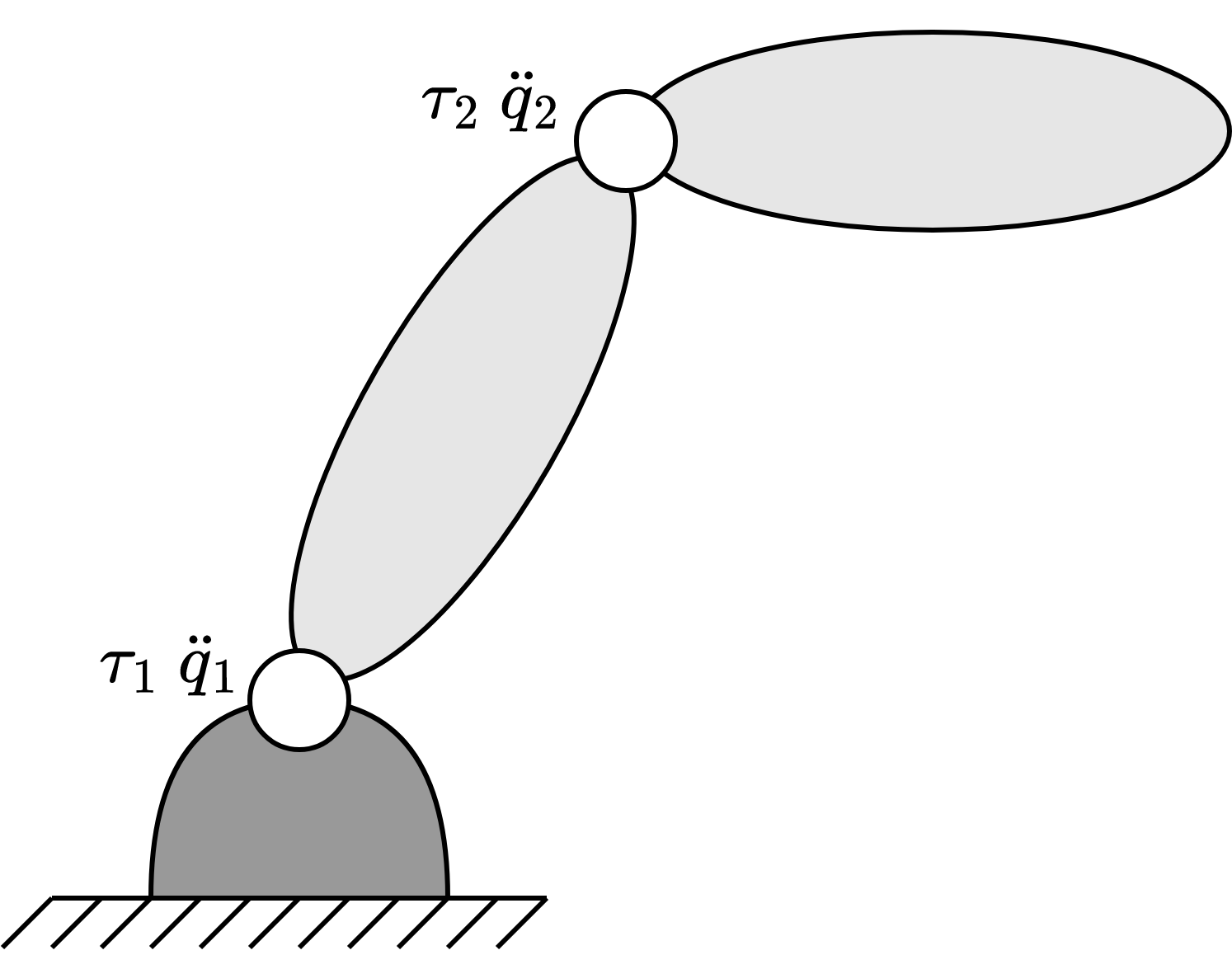

Inverse dynamics is a crucial problem in robotics, necessary for motion control systems, trajectory design, and optimization. It involves finding the forces required to produce a given acceleration in a rigid-body system that consists of bodies that do not deform or change shape during motion. To represent inverse dynamics, we can use the equation:

\[\tau = \mathrm{ID}(model,\ q,\ \dot q,\ \ddot q) = M(q)\ddot q + C(q, \dot q) \dot q + g (q)\]Here, \(model\) is the model description of the robot that contains kinematics, which are transformations between joints, and dynamical parameters like masses of links, their inertias, and the center of mass. \(q\), \(\dot q\), \(\ddot q\) are vectors of joint positions, velocities, and accelerations, while \(\tau\) is the vector of joint torques. \(M(q)\) is the position-dependent inertia matrix, \(C(q, \dot q)\) is the matrix of Centrifugal and Coriolis forces, and \(g(q)\) is the vector of gravitational forces.

The recursive Newton-Euler algorithm (RNEA) is the most efficient algorithm for computing inverse dynamics. It consists of two recursions: forward and backward. During the forward recursion, we calculate the velocity and acceleration of each body in the tree and the forces required to produce these accelerations. During the backward recursion, we calculate the forces transmitted across the joints from the forces acting on the bodies and the generalized forces at the joint.

Computing inverse dynamics in Pinocchio is straightforward. The following code snippet demonstrates how to do it:

import pinocchio as pin

import numpy as np

urdf_path = ''

model = pin.buildModelFromUrdf(urdf_path)

data = model.createData()

q = pin.randomConfiguration(model)

v = np.random.uniform(-np.pi, np.pi, size=(model.nv,1))

a = np.random.uniform(-np.pi, np.pi, size=(model.nv,1))

tau = pin.rnea(model, data, q, v, a)

Forward dynamics

Forward dynamics is the problem of finding the acceleration of a rigid-body system in response to given applied forces. It is mainly used for simulation. The equation that represents forward dynamics is:

\[\ddot q = \mathrm{FD}(model, q, \dot q, \tau) = M(q)^{-1}\big(\tau - C(q, \dot q)\dot q - g(q)\big)\]There are two methods to calculate forward dynamics: the slow system level method and the fast propagation method. In the following two subsections, we will discuss each of them.

Slow system level method

The system level method involves three steps:

- Calculate the bias force \(h(q,\dot q) = C(q, \dot q) \dot q + g(q)\);

- Calculate the inertia matrix \(M(q)\);

- Solve a system of linear equations for \(\ddot q\).

Steps 1 and 2 can be accomplished using the inverse dynamics algorithm: \(h(q, \dot q) = \mathrm{ID}(model, q, \dot q, 0)\) and \(M(q)\) can be constructed columnwise. The composite rigid body algorithm is a more advanced and faster algorithm for computing the inertial matrix. Overall, if the inverse dynamics algorithm is implemented and the computation time is not an issue, then the system level method is a good choice for calculating forward dynamics.

Here is an example of how to compute the slow system-level method in Pinocchio:

import pinocchio as pin

import numpy as np

urdf_path = ''

model = pin.buildModelFromUrdf(urdf_path)

data = model.createData()

q = pin.randomConfiguration(model)

v = np.random.uniform(-np.pi, np.pi, size=(model.nv, 1))

tau = np.random.uniform(-np.pi, np.pi, size=(model.nv, 1))

# Calculate bias force

h = pin.rnea(model, data, q, v, np.zeros(model.nv))

# Calculate inertia matrix

M = pin.crba(model, data, q)

# Solve for joint accelerations

a = np.linalg.solve(M, tau - h)

Fast propagation method

The fast method for calculating the forward dynamics is based on the articulated body inertia and is known as the Articulated Body Algorithm (ABA). In contrast to the usual inertia that maps velocity to momentum, the articulated body inertia maps acceleration to force. Articulated body inertias only depend on the inertias of the individual bodies and the constraints imposed by the joints, making them functions of joint position variables and not velocity variables or various force terms.

The ABA algorithm consists of three recursions: a forward pass, a backward pass, and a second forward pass. During the first forward pass, the algorithm computes velocities and bias terms. The backward pass calculates articulated-body inertias and bias forces. Finally, during the second forward pass, the algorithm computes the accelerations.

Here is an example of how to compute the forward dynamics using ABA and Pinocchio:

import pinocchio as pin

import numpy as np

urdf_path = ''

model = pin.buildModelFromUrdf(urdf_path)

data = model.createData()

q = pin.randomConfiguration(self.model)

v = np.random.uniform(-np.pi, np.pi, size=(model.nv,1))

tau = np.random.uniform(-5, 5, size=(model.nv,1))

a = pin.aba(model, data, q, v, tau)

Hybrid dynamics

Hybrid dynamics is a generalization of both forward and inverse dynamics. In hybrid dynamics, the forces are known at some joints, the accelerations at others, and the task is to calculate the unknown forces and accelerations. This approach is useful for introducing prescribed motions into a rigid-body system. The function that represents hybrid dynamics is:

\[\ddot q_{FD},\ \tau_{ID} = \mathrm{HD}(model, q, \dot q, \ddot q_{ID}, \tau_{FD})\]Similar to forward dynamics, hybrid dynamics can be calculated using either the slow system-level method or the fast method, which involves a combination of the RNEA and ABA algorithms. Unfortunately, Pinocchio currently does not have a fast implementation for hybrid dynamics. However, the RNEA algorithm can still be used to compute the hybrid dynamics.

To begin with, we can take the inverse dynamics equation:

\[M \ddot q = \tau - h\]and split the joint acceleration vector \(\ddot q\) into two parts: \(\ddot q_{ID}\) and \(\ddot q_{FD}\), where \(\ddot q_{ID}\) represents the joint accelerations which we know, and \(\ddot q_{FD}\) represents the joint accelerations that we need to calculate. Similarly, let’s split the joint torque vector \(\tau\) into two parts: \(\tau_{ID}\) which we need to calculate and \(\tau_{FD}\) which we know. Using the split acceleration and torque vectors, we can rewrite the inverse dynamics as:

\[\begin{bmatrix} M_{11} & M_{12} \\ M_{21} & M_{22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \ddot q_{ID} \\ \ddot q_{FD} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \tau_{ID} \\ \tau_{FD} \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} h_{ID} \\ h_{FD} \end{bmatrix}\]Now, we can rearrange the equation so that all the unknowns are on the left-hand side, and all the knowns are on the right-hand side:

\[\begin{bmatrix} -1 & M_{12} \\ 0 & M_{22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \tau_{ID} \\ \ddot q_{FD} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \tau_{FD} \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} M_{11}\ddot q_1 + h_{ID} \\ M_{21}\ddot q_1 + h_{FD} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ \tau_{FD} \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} \tilde h_{ID} \\ \tilde h_{FD} \end{bmatrix}\]From this final arrangement, it becomes clear that to solve hybrid dynamics, we need to perform the following steps:

- Calculate modified bias force using inverse dynamics equation: \(\tilde h = \mathrm{ID}(q, \dot q, [\ddot q_{ID}^T\ 0]^T)\)

- Calculate \(M_{22}\) (the easiest way is to compute full \(M\) and extract \(M_{22}\))

- Calculate unkonwn joint accelerations by solving \(M_{22} \ddot q_{FD} = \tau_{FD} - \tilde h_{FD}\)

- Calculate unknown joint torques \(\tau_{ID}\) via \(\tau = \tilde h + M [0 \ \ddot q_{FD}^T]^T\)

Here is an example of how to compute the hybrid dynamics using Pinocchio:

import pinocchio as pin

import numpy as np

urdf_path = ''

model = pin.buildModelFromUrdf(urdf_path)

data = model.createData()

n_id_joints = 2

n_fd_joints = model.nv - n_id_joints

q = pin.randomConfiguration(self.model)

v = np.random.uniform(-np.pi, np.pi, size=(model.nv,1))

a_id = np.random.uniform(-np.pi, np.pi, size=(n_id_joints,1))

tau_fd = np.random.uniform(-5, 5, size=(n_fd_joints,1))

a_tilde = np.vstack((a_id, np.zeros((n_fd_joints,1))

h_tilde = pin.rnea(model, data, q, v, a_tilde)

h_fd_tilde = h_tilde[n_fd_joints:,:]

M = pin.crba(model, data, q)

M22 = M[n_id_joints:,n_id_joints:]

a_fd = np.linalg.solve(

M22,

tau_fd - h_fd_tilde

)

tau_id = (h_tilde + M @ np.vstack((np.zeros_like(a_id), a_fd)))[:n_id_joints,:]

In conclusion, this post only provides an introduction to the complex and vast topic of robot dynamics. To gain a deeper understanding, it is highly recommended to read Roy Featherstone’s book “Rigid Body Dynamics Algorithms” and Junggon Kim’s paper “Lie Group Formulation of Articulated Rigid Body Dynamics”.